About Rembrandt Etchings

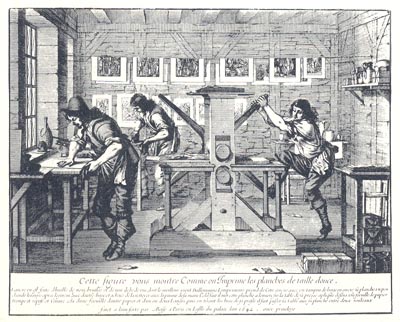

The process by which engravings and etchings were printed was itself the subject of this print made in the 1640s by a French artist, Abraham Bosse. The worker at the rear dabs ink on a metal plate bearing the design. The man at his side wipes off all of the ink except that in the design's grooves. As the man at right turns the handles of a press, a sheet of damp paper is pressed against the metal plate to pick up an inked impression. Finally, the fìnished prints are strung on a "clothesline" to dry. Rembrandt may have tackled the entire process singlehanded using a press similar to the one shown here to pull proofs of his etchings.

Many people are surprised to learn that Rembrandt's etchings, not his paintings, were responsible for the international reputation he enjoyed during his lifetime. When in 1660 the great Italian painter Guercino remarked, "I frankly consider him to be a great virtuoso," he was referring to the Dutchman's prints. The extraordinarily high regard Rembrandt's contemporaries had for his etchings was understandable, for in less than four decades he had pushed the relatively new medium to its expressive limits. While later printmakers tried to coax more from their etchings by altering the process, attacking the plate with new tools, and printing on unexpected surfaces, no one ever achieved greater results than Rembrandt attained with a simple etching needle and copper plates.

For Europeans of Rembrandt's day, a print, etching, engraving or woodcut filled a need that today is met jointly by a work of art and a news photograph. It gave them esthetic enjoyment and also satisfied their curiosity about distant places and people; it was, other than the printed word itself, the 17th Century's major means of mass communication. Publishers--and artists themselves--issued and circulated quantities of prints. Some took the form of simple broadsheets; others illustrated books; others reproduced privately owned paintings inaccessible to public view.

Thus Rembrandt's fame while he lived was greater as an etcher than as a painter (he did no engravings or woodcuts). The acknowledged master of the medium, he turned it into a wondrously flexible instrument of his art. Biblical themes, genre, landscapes, portraits, nudes, all these he found suitable for etching. As much in command of tools as of technique, Rembrandt sometimes employed even the V-shaped engraver's burin in his etchings, combining it with the fine etching needle and thicker dry point needle, as in the work opposite, for richer pictorial effects. Above all, Rembrandt's great gift as an etcher lay in preserving a sense of spontaneity while scrupulously attending to close detail. For him each etching, as the scholar K. G. Boon noted, "originated ...in the deeply felt need to make that particular print."

In etching as in painting Rembrandt worked with an inventiveness not seen before his day. In time 17th Century connoisseurs came to prize his etchings even more than his work in oil, and throughout his career his prints enjoyed a good international market. As late as 1669, the year of his death, when according to myth he was languishing in impoverished obscurity, a Sicilian nobleman brought 189 etchings from him.

Before Rembrandt's time the technique of engraving was more frequently used by printmakers than etching. In the former process, the artist works directly on a metal plate, usually copper; to create his design he laboriously cuts lines into its surface with a thin, diagonally sharpened steel rod called a burin. The excess metal thrown up beside the furrow cut by the burin is carefully scraped away before the plate is inked and prints are pulled from it. The visual effect of an engraving is one of neat, regular lines.

Self Portrait with Loose Hair

c. 1631

145 x 117 mm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In etching, the plate is covered with a protective coat of resin. The artist then scratches his design through the resin with a needle and immerses the plate in a bath of acid, which "bites" the metal wherever the resin has been removed. The action of the acid produces lines of a slightly irregular, vibrating quality; Rembrandt did not regard this as a drawback, however, but as a challenge.

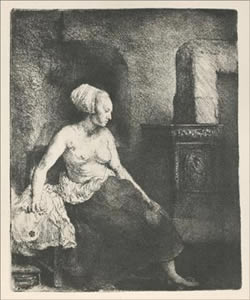

A copper plate lends itself fairly readily to change and correction. Lines may be removed by pounding and burnishing, and added at will; the etcher simply re-covers his plate with a fresh coat of resin and makes new scratches through it. Rembrandt sometimes took several years to finish a plate to his satisfaction, and he sold prints from the various states of his work. It is not uncommon to find as many as four or five different states of the same etching; sometimes the changes are minor, and sometimes radical. Almost from the start of his career, Dutch collectors were eager to purchase the variations. Houbraken, who seems to have been poking fun at the foolishness of some of these buyers, noted that the demand was "so great that people were not considered as true amateurs who did not possess the Juno with and without the crown, the Joseph with the light and the dark head and so on. Indeed, every one wanted to have The Woman by the Stove (bellow left) - for that matter, one of his least important etchings - both with and without the stove-key."

In engraving or etching the image is of course reversed-right, on the plate, becomes left on the sheet printed from it. Most printmakers take this into consideration by reversing their designs at the point when they transfer their preparatory drawings to their plates. Rembrandt, however, seems not to have cared much about this; his concern was with the quality rather than the pedantic accuracy of his work. Thus some of his etched self-portraits show him working with what seems to be his left hand although he was in fact right-handed, and some of his signatures appear in backward mirrorscript.

A Woman Seated Before a Dutch Stove

1658

227 x 185 mm.

He was so superb an etcher that critics were persuaded that he had discovered a secret process. "He had also had a method all his own of gradually treating and finishing his etched plates," wrote Houbraken, "a method which he did not communicate to his pupils. ...Thus the invention has been buried with the inventor." Indeed, etching has always been regarded as a somewhat mysterious proceeding, and there are "secrets" involving the ingredients in the protective coat, the strength of the acid bath and the time allowed for the acid to bite into the plate. Occasionally the physical or mental health of etchers has been impaired by excessive inhalation of acid fumes, and this, too, contributes to the aura of strangeness and mystery. But Rembrandt had no secret beyond his genius. He was the greatest etcher in the history of art, matched only by van Dyck in certain of his portrait etchings, by Whistler and by Degas in his rare ventures in the field.

Rembrandt's earliest etchings may be dated around 1626, when he was 20, and the very few surviving impressions of such a work as the Rest on the Flight to Egypt exhibit both his inexperience and his lively response to the medium. He had no thought of making his print look like an engraving, but used a free, scribbling stroke; the protective cove ing on his plates was soft, permitting him to move his needle with the fluidity of chalk or pen on paper. The Rest is unfinished and experimental, and to many eyes it appears to be a botched job that the artist might better have destroyed. However, the etching serves notice of what is was to come. As in almost all his work, Rembrandt approached his subject with great warmth, conceiving the Holy Family not in the traditional way but quite literally as a family: Mary feeds her Son while Joseph, who is often relegated to the background in such scenes, holds the dish.

Rembrandt's sense of humanity is even more evident in a group of small etchings ofbeggars and outcasts made in the late 1620s. In these he was considerably influenced in subject matter and even in pose by the works ofthe great contempory French etcher, Jacques Callot. Having seen at first hand the horrors resulting tram the Thirty Years' War, Callot produced a gallery of maimed wretches such as might have been found on any highway in Europe. The prints were widely circulated, and there can be little doubt that Rembrandt was familiar with them. PowerfuI as Callot's prints may be, however, they still contain a faintly satirical quality, as though the artist were asking the viewer, in a detached Gallic manner, "Are they not interesting?" Rembrandt's beggars and cripples are not "interesting," but full of suffering. They arouse a feeling of wrath at the plight of man, and it is plain that he identified himself with them: on an etched sheet of studies of about 1630 there appear the heads of an old man and woman, an aged beggar couple hobbling on sticks, and Rembrandt's face.

The Little Polander

1631

759 x 21 mm.

Within two or three years after his first efforts Rembrandt had become a master of etching. The portrait of his mother, dated 1628, is an extraordinarily penetrating character study, executed by the 22-year-old artist in a network of very fine lines that capture the play of light, shadow and air with a skill far exceeding that of Callot or of any Dutch etcher. The refinement of his technique appears to even greater advantage in a later portrait of his mother, in 1631, in which countless scurrying, hair-thin strokes are used to build up his chiaroscuro and texture. However, as in the total of Rembrandt's production during his Leiden years, delicacy appears side by side with boldness, even coarseness. In his oils of the period, the contrast may be seen by comparing the precision and polish of Tobit and Anna with the 1629 Self-Portrait, scored with the handle of the brush. In his etching, Rembrandt's muscular style is vividly apparent in another self-portrait of the same year, in which he experimented with the use of a blunt instrument, probably a broken or double-pointed one, exposing the correr beneath the coating with vigorous slashes like those in a spontaneous pen drawing. The twin currents of refinement and dash, of the smooth and the rough, emerge in Rembrandt's work from the very beginning and are by no means contradictory. They indicate instead the tremendous range of a young man who was able to accomplish more in a few years than many another artist achieves in a lifetime.

In the course of his career Rembrandt made scores, even hundreds of impressions from many of his approximately 290 plates. None of the etchings is larger than 21 by 18 inches; many are of postcard size or smaller, and one, The Little Polander, measures only three-quarters of an inch wide and two and one-quarter inches high. Rembrandt's income from the sale of his prints is impossible to determine, although the celebrated Hundred Guilder Print apparently was so called because an early collector was willing to pay that sum for an impression of it. Today, when a particularly fine impression of a rare Rembrandt etching changes hands, the price may be as high as $84,000, and in the present buoyant state of the art market it will doubtless go higher.

At least 79 of Rembrandt's original plates are still in existence. All are of thin metal, the thickest being only about one twenty-fifth of an inch, and many of them are worn or have been ruined by the reworking of later hands. Astonishingly, no fewer than 75 of the plates are owned by one man, Robert Lee Humber of Greenville, North Carolina, a retired international lawyer, who acquired them in 1938 in Paris but did not place them on exhibition for almost 20 years, during which time the question of their whereabouts continued to mystify Rembrandt scholars. In 1956 Mr. Humber permitted his treasure to be exhibited at the North Carolina Museum of Art, at once settling all the scholarly bafflement. The plates are genuine, and, as recent photographs show, a few are still in fine condition.